Understanding the Gender Pay Gap

by Lawrence M. Eppard

Partisans on both the left and right in the U.S. frequently make inaccurate claims about the gender pay gap. Faced with this onslaught of contradictory messages, it is no wonder that many Americans have a difficult time knowing what to believe.

At the Connors Forum we are committed to disseminating high-quality nonpartisan information to the American public around issues of societal importance. So what does the leading research actually say about the gender pay gap?

How the Gender Pay Gap is Defined

In the U.S., the gender pay gap is typically defined as the difference in wages between full-time male and female workers. It is often presented as a ratio. Stated this way, we would say that the gender pay gap in the U.S. today is around 83%.

This means that when you look at the average full-time female worker in the U.S., she earns about 83% of what the average full-time male worker is earning.

Data source: American Association of University Women. Stock images from pexels.com.

Table 1 below displays how much the gap varies from state to state.

The top five performing states are Vermont (91%), Hawaii (89%), Maryland (89%), California (88%), and Nevada (87%).

The bottom five are Alabama (74%), Oklahoma (73%), Louisiana (72%), Utah (70%), and Wyoming (65%).

Causes of the Gender Pay Gap

One of the most widely respected and frequently cited studies of the causes of the gender pay gap comes from Cornell University economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn.

Blau and Kahn’s quantitative analysis reveals that gender differences in occupation and industry together account for about half of the gap. When other variables such as gender differences in labor force experience are included, a little over 60% of the gap is accounted for (see Table 2 below).

Francine Blau explains:

“We have considerable occupational segregation by gender, and that explains about a third of the gap. Despite strong inroads into traditionally-male professional and managerial occupations, blue-collar occupations still remain heavily male while much office work remains heavily female. Men and women also tend to work in different industries, which explains about 18% of the gap. So together, occupation and industry explain about half of the gender wage gap. Among professional workers, women are more likely to be in relatively lower-paying jobs, such as elementary school teachers, whereas men would be more likely to be in higher-paying jobs, like lawyers or doctors. Women also tend to be more concentrated in lower-paying service occupations, like childcare workers. Gender differences in college major are really important and are related to the occupational differences. We've had equalization in terms of gender opportunities in education to the point that women are now exceeding men. But despite some convergence there are still sizable differences in college major and these are very closely tied to labor market outcomes. In STEM [science, technology, engineering, and mathematics] fields, for instance, women are particularly underrepresented. Labor force experience is another factor. Traditionally, women might have left the labor force for extended periods of time when they had small children in the home.”

Figure 1 below supports Blau’s remarks concerning gender and college major selection. Andrew Chamberlain and Jyotsna Jayaraman, whose data this figure is based upon, explain that:

“the biggest cause of today’s gender pay gap is that men and women sort into different jobs—men into higher-paying positions and women into traditionally lower-paying jobs. . . During college, men and women gravitate toward different majors, often due to societal pressures. This puts men and women on different career tracks—with different pay—after college. . . Many college majors that lead to high-paying roles in tech and engineering are male dominated, while majors that lead to lower-paying roles in social sciences and liberal arts tend to be female-dominated, placing men in higher-paying career pathways, on average. . . Nine of the 10 highest paying majors we examined are male-dominated. . . Choice of college major can have a dramatic impact on jobs and pay later on. Our results suggest that gender imbalances among college majors are an important and often overlooked driver of the gender pay gap.”

After accounting for men and women sorting into different occupations and industries, as well as differences in labor force experience, 38% of the gender pay gap remains unexplained. What might account for the remaining gap?

There are a variety of studies from other scholars that provide important insights. There is evidence from experiments, for instance, which shows that men are more competitively inclined, more likely to negotiate, and less risk averse on average when compared to women. Other survey-based studies have suggested that some combination of gender differences in agreeableness, self-confidence, extroversion, and the importance placed on money/work/family may contribute to the unexplained gap.

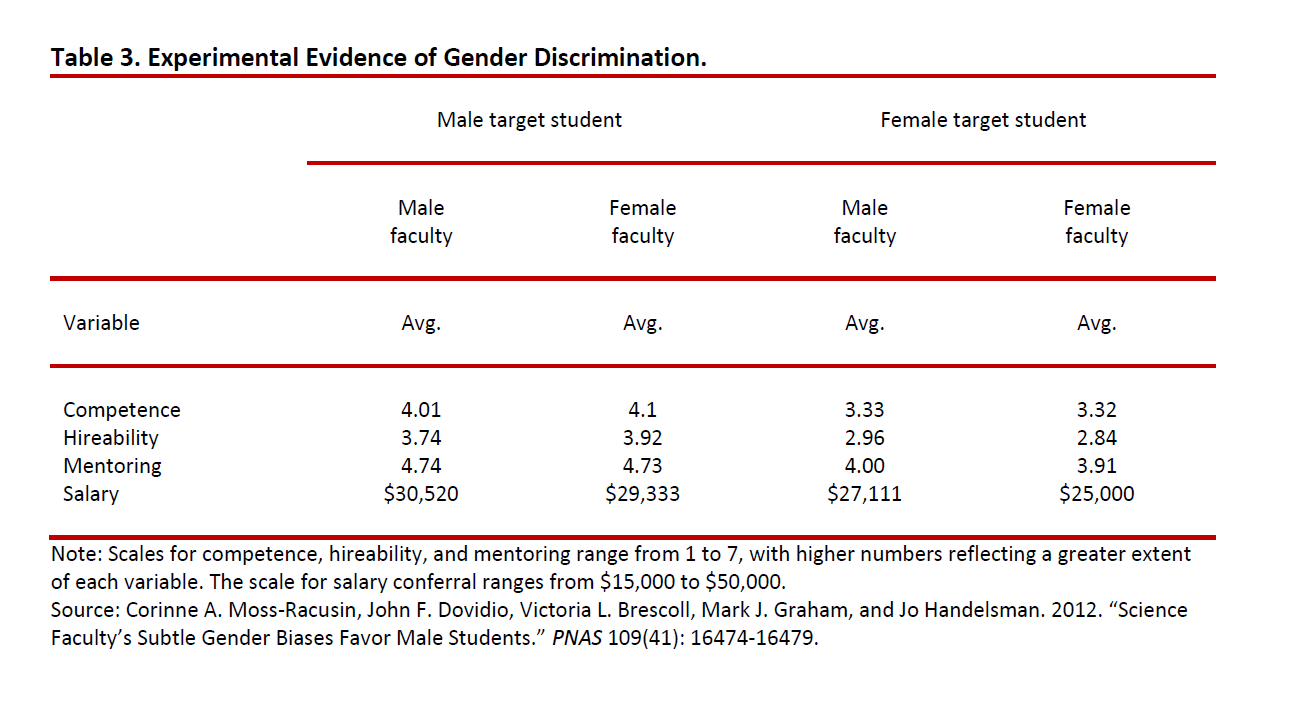

There is also experimental evidence that gender discrimination may still play an important role. In one notable experiment, the researchers had science faculty members from research-intensive universities rate the application materials of fictitious students applying for a laboratory manager position. The application materials were identical except for the names, which were randomly assigned as either male or female. Faculty participants rated the male applicant as significantly more competent and hireable than the identical female applicant, and offered more career mentoring and a higher starting salary to the male applicant. The gender of the faculty participants did not affect responses, as female and male faculty members were equally likely to exhibit bias against the female applicant. You can see the results of this experiment summarized in Table 3 below.

Here the researchers discuss the results of their experiment:

“Our results revealed that both male and female faculty judged a female student to be less competent and less worthy of being hired than an identical male student, and also offered her a smaller starting salary and less career mentoring. . . the current results suggest that subtle gender bias is important to address because it could translate into large real-world disadvantages in the judgment and treatment of female science students. . . It is noteworthy that female faculty members were just as likely as their male colleagues to favor the male student. The fact that faculty members’ bias was independent of their gender, scientific discipline, age, and tenure status suggests that it is likely unintentional, generated from widespread cultural stereotypes rather than a conscious intention to harm women. Additionally, the fact that faculty participants reported liking the female more than the male student further underscores the point that our results likely do not reflect faculty members’ overt hostility toward women. Instead, despite expressing warmth toward emerging female scientists, faculty members of both genders appear to be affected by enduring cultural stereotypes about women’s lack of science competence that translate into biases in student evaluation and mentoring.”

What Myths do Partisans Perpetuate?

There are a variety of myths that those on both the left and right perpetuate in the public discourse.

On the left, one of the most common that I hear is, “Women are being paid 83% of what men are being paid for the same work.” As our earlier definition makes clear, this is not what the gender pay gap indicates. It measures what average full-time male and female workers earn, but it says nothing of whether they are doing the same types of work.

One of the most common things I hear from those on the right is, “Once you take into account individual differences between workers, there is no gap at all.” What accounts for the unexplained portion of the pay gap is actually quite contested territory. Some of the factors may indeed be about the characteristics of individual workers—their level of competitiveness, for instance—while some factors may be outside of the control of individuals, such as discrimination. Furthermore, some differences that seem to be the result of individual choices may be at least partially impacted by forces outside of one’s control. While we all make choices, men and women don’t always have the same choices available to them.

Can the Gap be Reduced Further?

Research suggests that there are ways to further reduce the gender pay gap. One method would be through better family policies. In the words of Francine Blau, improving such policies would “make it as easy as we possibly can for American workers to combine work and family.”

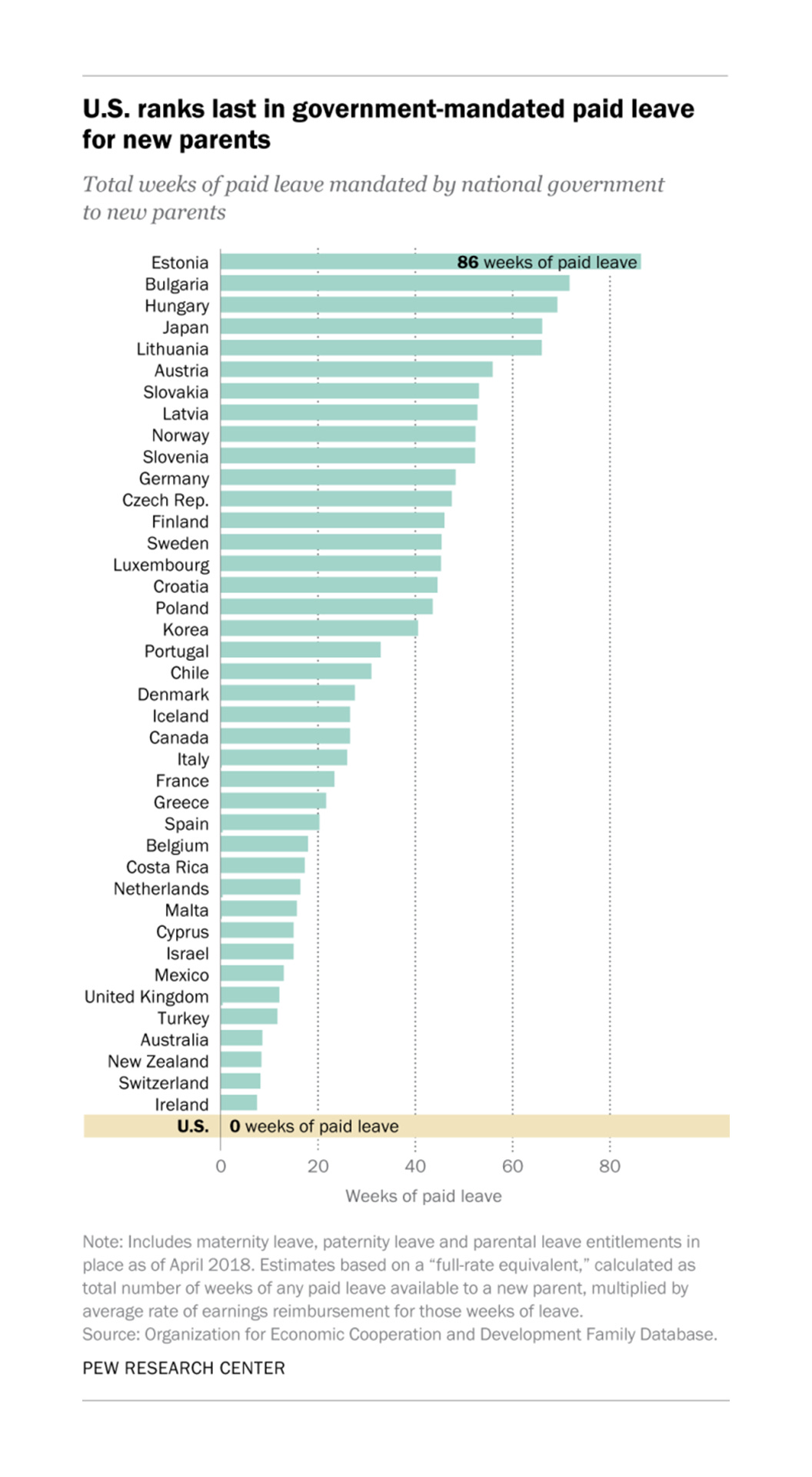

Such policies might include things like subsidized childcare and federally guaranteed paid parental leave. In the U.S., it is difficult for many families to find high-quality childcare that is affordable. On paid leave, the U.S. really stands out compared with other wealthy countries in not providing federally guaranteed paid parental leave. It also stands out among wealthy countries in terms of the amount of support that it offers to families with children generally (see Pew Research Center graphic and Figure 2 below).

As Francine Blau explains:

“The U.S. went from having one of the higher female labor force participation rates compared to other developed countries to having one of the lower rates. The crucial difference between the U.S. and these other countries was that they had much more generous parental leave than we did. That was a big factor in the U.S. slowdown. So that does suggest that we are pushing against some constraints in the balance between family and work. . . We certainly have way too little parental leave in the U.S. and our leave is not nearly generous enough. In terms of national legislation, Americans can take leave for 12 weeks and it is unpaid, while the average for the other countries in our data would be about a year, and all of them are paid. The U.S. is indeed off the charts in that respect. Childcare is also a very important part of the formula. . . It makes it easier for women to be attached to the labor force, and it’s not pulling people in separate directions between home and work. . . So those are some key policies, both subsidized childcare and paid parental leave. In terms of overall gender equity in the labor force, continued strong enforcement of anti-discrimination laws is very important as well.”

Research shows that, before couples have their first child, the gender pay gap is much smaller. Once the first child arrives, women often “take their foot off the pedal” more in their careers compared with men—given that they are disproportionately responsible for housework and childcare—which contributes to reduced earnings over time (see Figure 3 below).

Policies that help ease the work-family balance are among a number of options available to us if we choose to continue to reduce the gender pay gap in the U.S.

Cornell University economist and gender pay gap expert Francine Blau explains her research findings:

A shorter version of this article first appeared in The Sentinel newspaper on January 21, 2022. It has been reprinted here with permission.

OECD figure (Figure 2) used in accordance with their guidelines. Pew Research Center graphic and American Economic Association figure (Figure 3) reprinted here with permission. All other tables and figures created by Lawrence Eppard based on existing data which has been cited accordingly above.

Pexels stock images used according to their guidelines.

If you like what we are up to, please consider subscribing below! And don’t forget to visit us at ConnorsForum.org.